By Patrick Moriarty –

It’s always difficult call these things, but I think (and hope) that the last couple of weeks may, in retrospect, come to be seen as a watershed on the long and painful road to achieving universal access to water and sanitation services worthy of the name.

The potential game changer is the decision of the Dutch government and its development agency, DGIS, to start requiring recipients of finance for WASH service provision to explicitly commit to service delivery: at an agreed level over an agreed time-frame (10 years) – something that they are calling a sustainability clause.

As colleague Carmen da Silva wrote in her recent blog, even the possibility of a sustainability clause has been stirring things up in the last couple of months – within my own organization IRC as much as within the wider WASH community. Which, given the often semi-comatose state of our sector is, of itself, a good thing. But now it’s official. DGIS’s Dick van Ginhoven spoke several times during the Stockholm water week to confirm that the Dutch government is committed to some sort of clause. And that whoever wants to access the 100 million Euros or so of potential Dutch new funding is going to have to give some sort of assurance that not only will they use it to help provide shiny new infrastructure – but that the shiny new infrastructure will provide an agreed minimum level of service for at least ten years. So, a clause accompanied by a large carrot – one that will put wind into the sails of movements like Everyone Forever that are already explicitly committing to long-term service delivery.

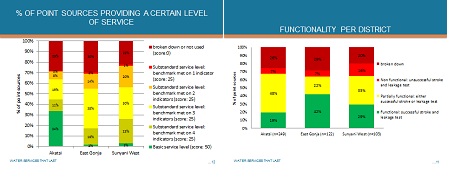

Various colleagues have said that this looks a blunt tool for what we all know is a highly complex problem. And yet, complex systems theory tells us that sometimes only a blunt tool (or a large perturbation) is capable of breaking open a system – pushing it from an existing to a new equilibrium. And rural WASH is badly in need of a new equilibrium. How else can we explain a situation where so many of us have been talking about sustainability for so long – and where we still have so little evidence of progress – and so much evidence of the opposite. These two slides from a presentation by my colleague Marieke Adank are based on work from Ghana and are illustrative: >30% of surveyed infrastructure not functional, and as little as 2% providing the basic level of service for which it is intended).

Marieke’s presentation drew rave review from attendees at Water for People’s exciting ‘Judge us by our outcomes’ session during World Water Week. You can see the whole presentation here and we’ll very shortly releasing a series of fact sheets based on the data presented- which I’ll blog on at the time.

The sector is locked into a pattern of behavior that leads to the wrong outcomes. It is driven in this by, among other things, policies that focus on counting the number of people newly served – like the original DGIS commitment to provide 50 million previously unserved people with access to WASH services. Not in itself a bad thing of course – as the achievement of the water MDG confirms – but one with the unintended (emergent) consequence of overemphasizing new construction at the expense of ongoing service delivery. DGIS proposed sustainability clause seeks to redress this situation by putting the focus of their grantmaking squarely where it should be: on delivering WASH services over time.

Of course there is no way of knowing exactly how this will work out in future. The clause is a blunt instrument – policy at this level invariably is. There are layers of detail that need to be worked out, and of course, there are attendant risks. However, in a sector that is still – in many countries – massively aid dependent it seems a stretch to suggest, as some have, that placing a measure of outcome accountability on implementers will fundamentally undermine the compact between government and citizen (a compact currently honoured largely in the breach). Put another way – what is the underlying logic that says that relying on grants for capital investment promotes aid effectiveness, while relying on them for operational expenditure or capital maintenance does not?

For me – and it is a personal opinion – the news that DGIS intends to implement some sort of clause is a champagne moment. Not because I’m unaware of the risks but because, finally, someone has had the courage to accept that water and sanitation are services, that it is the quality (or level) of the service over time that is important, and that to achieve a service you have to spend your money on more than just new infrastructure.

Perhaps most exciting given this – more champagne! – is that DGIS is also aware that this isn’t a cheap option. As van Ginhoven said at IRC last week (see Carmen’s blog) “the argument that this will be more expensive is the wrong argument, we prefer to put more money up front than to continually invest in rehabilitating failed infrastructure”. DGIS know that they are setting the bar high, and they are prepared to put their money where their mouth is.

All attendant risks to one side this brave experiment will mean that, if nothing else, in ten years’ time we will have clear evidence at scale of what it costs to provide a basic level of WASH service to the poor: in fact as opposed to community management fantasy. Whether we – or national governments – will then feel that the cost is justified is another question.

Reblogged this on patrickmoriarty.

Big organizations by necessity function through big, blunt instruments. This is great news. Let’s hope that DGIS also commits to convincing fellow bilateral donors and IFIs to adopt similar clauses.

Let’s hope that other bilaterals can learn/be inspired by this brave move. AusAID has started to address the sustainability challenge through the criteria it sets in its new Civic Society WASH fund, but these are still ‘soft’ and lack the hard stop that DGIS is putting down

A ‘sustainability clause’? There has been some debate on the airwaves recently about the demands that donors may increasingly place on grant and loan recipients to ensure that water services are sustained over time. I was personally in a meeting at the Stockholm Water Week in August 2012, during which the Dutch Government’s (DGIS) requirement for a ten-year ‘sustainability clause’ was reiterated, a position which apparently AusAid supports in principle, but with a less demanding 3-year time horizon. Subsequently Patrick Moriarty of IRC blogged in support of these donors’ stance, admitting that such a clause represents ‘a blunt instrument’, but nevertheless welcoming it as a way of waking up the water sector to the importance of water supply as a service rather than merely a capital investment in physical assets.

Sharper instruments? While having a great deal of sympathy with both the donors’ position, and the stance taken by Patrick Moriarty, I suggest that a more subtle approach is needed. Better ways exist to bring about this shift from gift to service, from ‘the easy bit’ of water development to the hard slog of service provision.

Perverse behaviours? Patrick Moriarty claims that “the sector is locked into a pattern of behaviour that leads to the wrong outcomes”. I agree. But underlying all behaviours are assumptions, beliefs, habits of thought, and indeed an entire sectoral culture which result in those behaviours. I believe there are several incorrect assumptions and thought-patterns about the way we do things now, which need to change. I will mention one, and more fully discuss a second.

Services not taps alone. The first big change is of course from development as capital investment (only) to development as sustained service. This has been very fully addressed by others, so I will say no more about it here.

Roles. The second change which I believe is needed is about how we see the roles of the various stakeholders. Right now we believe that Governments make policy, regulate and monitor; local Government organisations and NGOs implement, either directly, through the private sector, or through local NGO partners; communities utilise the services provided, but take on complete responsibility for maintenance and repair. Oh yes, and donors … donate.

Donors should not only donate. We pay lip service to the idea that ‘we are all in this together’, but the idea that any of the players involved can simply ‘do their bit’, stand aloof, and then criticise others for the failures of the system, is simply not good enough, in my view. Development creates inter-dependence; it doesn’t make one part of the system self-reliant. If communities receive better (closer, more reliable, higher quality) water supplies, they need assistance from local Government and/or the private sector and NGOs to maintain those services. In turn local Government needs the professional and competent support of central Government to do its job. Can the donors simply attach conditions – time guarantees – to their grants and stay aloof? I think not.

Collaboration. So what should the donors be saying or doing? In my view they should be getting down on the ground and working in the same fields as the rest of us. Not standing above, spreading seed and holding us to account when that seed fails to thrive. Agricultural work is hot and sweaty, dirty and hard. It is prone to disasters posed by weather, pests and diseases. Similarly our attempts to provide sustainable water services in low-income countries – with communities which may never have enjoyed such services, never had to manage modern water supply technology, never had to handle communal revenues at the levels needed to keep such systems working – are prone to all sorts of difficulties. Are we all in this together or not?

Reorienting donors. Donors who commit (a) to join hands with the other players for as long as it takes to develop sustainable service models, and (b) who really take the trouble to understand the issues involved on the ground; donors who take on their share of the responsibility to find solutions which will go on working; those are the donors which impress me. Such approaches represent for me a sharper instrument than the ‘blunt stick’ of donor conditionality and outcome-based largesse.

Donor responsibility. Donors come in all shapes and sizes: the lending banks, the bilateral and multi-lateral agencies, the philanthropic foundations, and some of the international NGOs (the ones which do not implement directly). None is exempt from the responsibility to play its full part, with the user-communities, local Governments, private sector and NGOs, and Governments, in assuring that water services become sustained and permanent.

Sustainability is about risk. Finally, the very nature of sustainable service as a concept means that it is about the continued (future) functioning of something that is working now. Assessing sustainability is about a present assessment of the risk of things going wrong in future. That is why all parties must commit to collaborate for as long as it takes for that risk to recede to insignificant levels. Then and only then can some of the parties withdraw and move on.

Richard Carter

11th September 2012

Couldn’t agree more with the ambition – donors SHOULD indeed get down and dirty with everyone else. Unfortunately, the trend of the last 30 years for governments to outsource EVERYTHING – including development cooperation – from implementation to strategy development weighs against this.

Anyone who’s spent time on a sector working group with harassed and well meaning aid bureaucrats who are handling WASH – together with roads, women’s affairs etc. – supported by an ever changing roster of consultants – knows the problem. Increasingly the multilaterals are the last group who maintain serious technical capacity in country – and who can bring these sharper instruments to bear.

[…] mentioned some cool new outputs from IRC’s Ghana programme in my previous post. These factsheets present a rich picture of water services and their governance based on a […]

Hmmm…

reading this has given me chills… another condition for funding? Really?

In all the studies done so far in Ghana on sustainability, I am yet to see any that fully digs in to find out why 30% of the systems fail. Is it that we are using the wrong technology, unsustainable community management systems, overly expensive interventions that the local authority is unable to maintain, sheer negligence by community and authorities etc? In my view the ‘branches’ of the problem is evident for all to see and comment on but what about the root causes?

Will a Clause signed by other donors or even countries ensure sustainability of the systems? or are we carrying out yet another experiment in developing countries? Then again, this is under the presumption that my country will as usual continue ‘solliciting’ for money to fulfil it’s primary role of providing water and sanitation for it’s populace.That even though the GDP has gone up so much, the nation will still continue to rely on such finding sources for WASH activities….hmmmmm…..

Question… what if my country uses it own funds or BRIC funds (which have fewer conditionalities), what happens to the Sustainability Clause? or better yet should it ignore sustainability all together?

I still have many questions, but as the title conotes’ that’s no excuse for being timid’. I’m not sure I will call my position timid.. maybe cautious not to derail all the effort of partnership, ownership of shared development concepts, mutual respect and accountability….

[…] radical changes in its approaches so as to improve sustainability. The boldest one is arguably the sustainability clause, which would commit recipients of Dutch aid to be responsible for 10 year sustainability of service […]

[…] that DGIS seeks to include in its contacts with implementers. The pros and cons of this have been widely debated . A key component of the clauses is to have sustainability checks as a way to verify […]

[…] my friend and colleague – and now the new Director of IRC – Dr. Patrick Moriarty, who wrote a great blog that celebrated the introduction of the clauses as a ‘champagne moment’ for the sector. He said […]

[…] and have to be emptied”. The announcement of this clause in Stockholm last year was something I blogged about enthusiastically at the time – so it was great to have this check in on progress a year […]

[…] would make reference to the commitment to ensuring sustainability of services, as demanded by the Sustainability Clause that the Netherlands has been spearheading. Yet, that is not the […]

[…] A number of donors are starting to turn their attention to the sustainability problem and are asking recipients of funding to take a wider view of what it takes to deliver services. DGIS, the Dutch aid agency, has instituted a sustainability clause in an effort to encourage recipients of Dutch funding to ensure that infrastructure will continue to provide an agreed level of service for at least 10 years. Whether the clause will function as intended remains to be seen, but it is a step in the right direction (see Patrick’s blog post). […]